In my last blog I wrote about a book that introduced me to the concept of collapsology. While the label is novel, the phenomenon it describes had already been lurking somewhere in my peripheral awareness, and as sometimes happens, finding a good conceptualization for an amorphous gut feeling helps make sense of that feeling. So, I decided to take a deeper look at the concept. Here’s what I’ve found so far.

Origins

As often happens, first there is a phenomenon that many people, independent of one another, recognize and try to make sense of. At some point one (or in this case three) of them comes up with a label that captures the essence, and thus the concept is born. Subsequently, regardless of whether or not the label is used, all approaches exploring the same phenomenon can be retrospectively clustered under the theme, making it easier to create a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

In the case of collapsology, the label was born in two books, “How everything can collapse” by Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens, and “Another end of the world is possible” by the same authors complemented with Gauthier Chapelle. However, at the same time these books were taking their forms in France (in 2015 and 2018 respectively), in UK Jem Bendell was coming to the same conclusions subsequently materializing in his Deep Adaptation viral paper, (2018) and in Germany, Fabian Scheidler was releasing his book “The end of the megamachine” (2015).

While the European books are painstakingly factual, in US, Naomi Oreskes and Erik M Conway had just released their short semi-fictional story, “The collapse of Western Civilization” (2014), which took the form of a historical research report written in 2393, exploring the collapse that took place around 300 years before. In it, the future researchers ponder the paradox of why, while there was ample knowledge and requisite means, did the historical actors not act in time to prevent the catastrophe, and why, when they did act, did they choose the means that escalated the problems?

While the list is not comprehensive (for example, test what books the Amazon AI recommends for you when you first search the above titles, or go to the collapsology portal for more reading tips), it seems that around a decade ago, many long-term sustainability researchers came to the same conclusion: the collapse of this civilization is inevitable. Reading the news of today, seeing the environmental data of the past ten years, and experiencing the currently prevailing political sentiments unfortunately does little to prove them wrong. Quite the contrary – what we’re seeing is even crazier than what the imaginary researcher of 2393 identified as the pinnacles of folly.

What it is

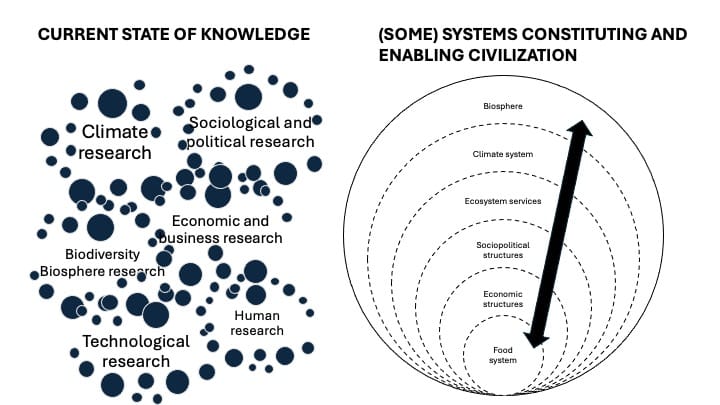

At its core, collapsology is about integrating knowledge about the systems that constitute and enable civilizations, drawing conclusions based on the status of the system of systems, and reflecting honestly the implications of those conclusions. While grounded firmly in science, it swims against the mainstream approaches in two critical ways, the first of which is depicted in the following figure. Collapsology seeks to synthesize knowledge from diverse disciplines instead of aiming at advancing isolated knowledge about any individual issue.

The scientific mechanism born around the Enlightenment was at its core about analysis – in other words, about separating an entity into its components (from Greek analyein, “to loosen, dissolve, resolve into constitutive elements”). Half a millennium on, and the mechanism is visible not only in the study of any individual phenomenon, but in the very structure of science. The number of disciplines, research streams, approaches and schools of thought is simply astounding: we have amassed vast knowledge about the most minutiae detail of everything we have ever thought to scrutinize.

The paradox is that the mechanism that yields us vast amounts of detailed knowledge renders that knowledge largely useless. Knowing how the heart functions does not help without understanding its role in the body. Being able to take an engine apart does not help unless one knows its role in a car. Usefulness of knowledge requires synthesis (from Greek syntithenai “to put together”), the ability to see the relevance of one titbit of information, to connect it to other parts of the whole, and to understand the purpose of that whole in an even larger whole.

Collapsology is a fundamentally transdisciplinary attempt to try to put together knowledge about the status of the world to assess the genuine sustainability of our current way of life. Its instigators are all (sustainability) scientists from diverse fields, so the appreciation of scientific knowledge is at its heart, but the idea is not to create more knowledge of any singular issue, but to try to see how the knowledge we have of the biosphere, the climate, the ecosystem services, the sociopolitical and economic structures, pathways and trajectories, and the very basic needs of the human animal looks, when viewed as a complex system of systems, a whole.

The results of this attempt create the second way collapsology differs from mainstream science. It does not believe in progress, linear or otherwise. Instead, it takes as granted that based on the synthetic knowledge about status quo, the days of this way of life are numbered. Our civilization is collapsing – as did so many others before. The acceptance of this reality creates the very purpose of having the concept, a mutual umbrella under which to shelter: if we accept that a collapse is underway, towards what should we orient our daily efforts – what should we do as individuals and collectives?

What it is NOT

Collapsology is not about alarmism or doomsday prophecies. It does not evoke Hollywood imageries of apocalypse nor does it promote survivalism. It does not seek media attention or popularity, aspire to gather followers, amass power or form trends or cults. It owns no crystal balls, makes no claims about possessing the ultimate truth of the futures, cannot predict.

Collapsology is neither about running around in streets shouting “The End is Nigh!” or about hiding under the bed awaiting for the last person to turn off the lights. It is not about making a stellar career based on first mover advantages of exploring a novel concept. Nor is it an attempt to pave way for gloating, for becoming the one to say “I told you so!”

But most of all, it is not about giving up. It is not about hopelessness or meaninglessness. Quite the contrary.

So, what should we do? (Three categories of collapsology)

The first thing to understand is the very personal, even intimate nature of collapsology. After all, if one accepts that our civilization is collapsing around us, it evokes a storm of feelings. What about me, my children? How can I move on?

Collapsology is a sphere the entering of which requires personal reflection, a way to find peace based on awareness and acceptance (in contrast to willful ignorance and denial most of us rely on to get through the day). All of the authors emphasize the importance of honest reflection of priorities: what do you (and I) want to really spend our days on? What do we consider genuinely valuable, and how does our mundane life reflect that? Is there room for making our normal day more meaningful? Towards what do we want to orient our everyday actions?

This process of personal reflection and acceptance is a notable theme in collapsology – indeed, it is the carrying theme of the whole book, “Another end is possible”, and a notable part of Bendell’s “Breaking together”. However, after one has come to terms with the inevitability of the collapse, new avenues open. Considering that the instigators of collapsology are all sustainability scholars, after acceptance, they have all turned outwards and pondered what type of knowledge could be useful when we drop the narrative that through human ingenuity, the calamities can be avoided? Subsequently, depending on the individual interests, the knowledge integration approaches seem to be divided into three wide categories.

Category 1: How did we end up here?

First of all, there is much knowledge to be integrated to paint a fuller picture of the trajectories that have led us to this situation. Combining older research about the causes of past collapses (for example through leaning on Joseph Tainter’s pivotal work, borrowing ideas from Jared Diamond or adopting a critical lens to our linear stories about past like Davids Graeber and Wengrow do ) with critical scrutiny of the rise of our current economic system, power structures or basic assumptions of the role of human animal in the wider biosphere, the collapsologists attempt to provide at least a documentation of what the humanity might not want to repeat.

For example, the “End of the Megamachine” takes a millennia spanning view in its attempt to paint a picture of the main reasons we now find ourselves at this juncture. It starts by delving the mechanisms of power: physical, structural and ideological. Of these the physical power is most easily grasped (after all, if someone points a gun at me, I do as they say), but the other forms actually underpin societies. Structural power emerges, because I live in a society where I have to work for salary in order to eat, whereas those accepted structures are actually built on ideological power. Just like the medieval Catholic Europeans gave power to the priests because they believed them to be the messengers of God, in possession of their salvation, we contemporary Westerners give power to the economic structures because we believe in the salvation promised by the story of economic growth.

Regarding power, a highly interesting viewpoint emerges in “To govern the globe”. Based on the analysis of the rise and fall of the past Iberian (circa mid 15th – early 19th century) and British (early 19th century – aftermath of WWII) empires, the story of the US empire so far, and the signals arising from the millennia old Chinese empire, it claims that the (at least some) current geopolitical power players have accepted the inevitability of the coming collapse, and are actually engaged in fortifying their positions to rise to power after it. A similar notion can also be found in “Breaking together”, albeit with a slight difference: in the latter it is the financial power of today that seeks to seize power, not the traditional geopolitical actors.

These thoughts lead to the second category.

Category 2: Underpinnings of future societies

Who should hold power in the future societies is one aspect of a wider mission to outline such underpinnings that might carry a more sustainable civilization. For example, in “Another end of the world is possible”, the authors suggest that instead of thinking about the Maslowian needs as a pyramid, a hierarchy, a more realistic and humane depiction would be to see the different types of needs as legs on a table. For a human to be human, not a mere bundle of biological reflexes, the table needs support from the leg of basic needs (sustenance and shelter), the leg of safety (physical and psychological), the leg of social needs (love, belonging, esteem) and the leg of self-actualization (individual meaningfulness). How would such a society look like that would take each of these needs equally seriously?

This category includes also discussions of the role of the human in the biosphere, with calls to explore the possibilities of a less anthropocentric approach to organizing our societies. Anthropological examples abound: believe it or not, we humans have already had societies with better chances of co-existing with the other parts of the planet.

Personally for me, the nature of a genuinely sustainable economic system is an intriguing dilemma. (BTW, in my next blog I’ll explicate why the current economic system is fundamentally incompatible with both humanity and the planet.) The future survivors need to rethink the respective values of such issues as property and ownership, human rights and freedom. They will also need to reconsider the pros and cons of having money, maybe reinvent it, maybe renounce it.

Of course, one might ask the point of envisioning novel societies if the starting point of such visions is the inevitability of collapse, i.e. calamities, disasters and catastrophes. Why should we bother – let the future survivors figure out the mess as they best see fit! The third category answers this.

Category 3: Adaptation and mitigation

Put simply, while the collapse is inevitable, the severity and timing of the calamities is not only unknown, but inequal both geographically and temporally, and dependent on the actions we today take. We cannot avoid the problems, but we can try to make them less severe, prepare for them better and create strategies to adapt.

Many of the sustainability efforts now underway within the narrative of prevention are highly useful even if their main aim is unreachable: every species we can save, every percentage of a grade we can shave off from the rising temperatures buys us time and saves lives. On the other hand, some of the efforts can be even harmful (a popular theme in science fiction, by the way – ask me for reading tips ), and we should critically assess the merits and risks included in all actions against the backdrop of coming collapse. After all, there are no problems so severe that human thoughtlessness, ignorance and stupidity could not make worse.

At best, we might be able to leave the survivors not only a more inhabitable planet, but also some insights and ideas of how to cope, how to rebuild, what to cherish, what to avoid. The third category of collapsology aims at achieving this.

Moving on

I personally find the collapsologist approach welcoming, even comforting. Because of that I actually enlisted a few fellow BIODIFULers to join me in an interactive round table discussion taking place next fall in Science for Sustainability conference in Helsinki. If you’re intrigued, come look us up, and join the discussions!