Over the past two decades, sustainability has become one of the central themes in finance. Sustainable finance has gained momentum in both practice and public policy, aiming to guide capital toward long-term economic transformation. In this process, environmental risks have become a central concern, and significant effort has been devoted to integrating them into investment and financing decisions. In practice, however, environmental risk in finance has largely focused on climate change. While this focus has significantly advanced climate finance, it captures only part of the broader ecological challenge that firms and markets are facing.

The environmental pillar of sustainable finance extends beyond climate change. According to the European Commission, it also includes biodiversity preservation, pollution prevention, and the broader protection of natural systems [1]. Among these dimensions, biodiversity stands out as both fundamental and underexplored. Biodiversity, the variety of life on Earth, underpins economic activity by providing food, materials, medicine, energy, protection from natural disasters, and cultural and recreational benefits. Yet biodiversity is declining at an unprecedented pace, with up to one million species estimated to be at risk of extinction [2]. This decline threatens not only ecosystems but also firms, supply chains, and entire economies that depend on healthy, resilient natural systems. Protecting biodiversity is therefore not only an environmental priority but also an economic necessity.

In this context, biodiversity finance has emerged as a new frontier of sustainable finance. It focuses on how biodiversity-related risks and impacts affect financial decisions, and how financial systems, in turn, influence biodiversity outcomes. Attention to biodiversity finance has grown in recent years, particularly following the 2022 UN Biodiversity Conference and the adoption of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. Despite this momentum, biodiversity finance remains underdeveloped in financial research. There is still no widely accepted framework for measuring, pricing, or integrating biodiversity-related risks into financial decision-making [3]. This challenge is further complicated by the fact that biodiversity loss spans multiple ecosystems, species, and local conditions, making it far more difficult to quantify and model, with lower tractability than climate change or emissions [4].

Biodiversity and Finance: Two-Way Relationship

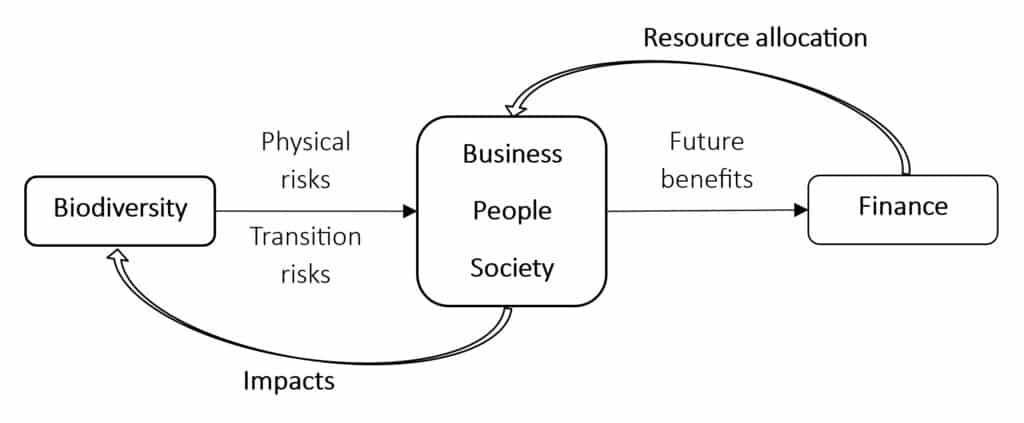

Biodiversity and finance are closely linked because economic activity depends on nature, and finance determines which activities receive capital and resources. This interconnection creates a two-way relationship. Biodiversity loss affects financial outcomes, while financial decisions shape the future of biodiversity.

On one side, biodiversity loss creates real financial risks. These include physical risks, such as the loss of ecosystem services on which businesses rely for production, and transition risks, such as tighter environmental regulation, shifting consumer preferences, and increased investor scrutiny. Biodiversity declines can lead to higher operating costs, supply disruptions, reduced profits, and greater uncertainty, underscoring biodiversity’s relevance to corporate strategy and investment decisions.

On the other side, finance plays a key role in addressing biodiversity loss. Financial markets determine where money flows through lending, investment, or capital allocation. Continued funding of activities that harm ecosystems can accelerate biodiversity loss and increase long-term financial risks. In contrast, directing capital toward nature-positive activities can support ecosystem protection and long-term resilience.

From an investment perspective, this connection is natural. Investing means committing resources today in the expectation of future benefits. Taking a broader view over the long term, those benefits are not limited to financial returns but also include quality of life, community well-being, and economic stability. From this perspective, aligning investments with ecological sustainability is not outside the scope of finance. It is central to it. Healthy ecosystems form the foundation for long-term economic and social benefits, making biodiversity an essential consideration in investment and capital allocation decisions.

First Evidence That Markets Care

Early research suggests that biodiversity is beginning to matter in financial markets, although the evidence is still emerging. Surveys indicate that many firms now view biodiversity-related risks as financially material [5]. Empirical studies show that firms exposed to biodiversity risks adjust their financing behavior, for example, by relying less on short-term borrowing [6] or facing tighter access to trade credit [7]. Market reactions to major biodiversity-related events, such as the Kunming Declaration and the launch of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures, also suggest that investors may penalize firms with large biodiversity footprints [8], at least in the short term.

These responses indicate growing awareness that biodiversity loss can have financial consequences. However, much of this attention appears to be driven by uncertainty, particularly around future regulation, litigation, and reputational risk, rather than by an in-depth and consistent understanding of how biodiversity affects corporate value.

At the same time, far fewer believe that investors systematically assess how biodiversity risks affect cash flows, firm value, or the cost of capital [5]. Some commonly used biodiversity indicators provide little additional information beyond basic firm characteristics, such as company size [9]. Existing research is also constrained by short sample periods and limited data availability, making it challenging to separate biodiversity effects from broader economic shocks or market volatility in recent years. Concerns have also been raised about selective reporting and a focus on statistically significant results rather than broader implications.

In Search of Clarity

It is undeniable that environmental integrity, and biodiversity in particular, is fundamental for economic and social prosperity. However, there is little guidance on how biodiversity fits into economic and financial models. At present, despite some conceptual progress, for example, The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review, there is no widely accepted framework for systematically integrating biodiversity into the functioning of the economy or financial markets. Too often, the discussion stops at the assertion that ”nature is our most valuable asset,” without explaining how this value enters real economic decisions and outcomes in ways that are measurable, verifiable, and operational, remaining largely illustrative.

Financial and economic decisions rely on quantification. Investors, firms, and governments use models to interpret reality, design policies, evaluate trade-offs, and anticipate outputs. Effective strategy and policy implementation require more than good intentions. They need a solid understanding of relationships between variables and a way to weigh biodiversity concerns against other urgent challenges, such as employment, poverty, economic development, social welfare, or geopolitical conflict. Without a framework that embeds biodiversity into models of economic behavior and financial decision-making, biodiversity remains outside the core of these choices. In that case, calls for biodiversity preservation become aspirational rather than actionable, describing an ideal world rather than the constrained reality in which decisions are made.

At a practical level, biodiversity finance also lacks widely accepted methods for defining, measuring, and pricing biodiversity-related risks and impacts, as well as the mechanisms underlying them. Finance requires accurate, comparable metrics, but until now, there has been no single, widely accepted measure of biodiversity. Existing approaches fall into three broad groups: company reports and news that capture attention to biodiversity issues, scientific models that estimate how business activities affect land use, water, and ecosystems, and national indicators that describe overall environmental conditions of specific areas. Each approach captures part of the picture, but they often lead to different conclusions. This disconnect, together with the lack of scalable, economically meaningful data, makes it difficult for financial markets to integrate biodiversity into assessment and capital allocation.

Biodiversity finance has moved from neglect to awareness, but not yet to clarity. Without fundamental frameworks and models, this awareness cannot translate into effective capital allocation. Making biodiversity a comprehensible and measurable feature of financial and economic models is therefore a cornerstone for guiding real financial decisions and allocating capital and resources efficiently in support of long-term sustainability.

Nam Vu is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Biodiversity Unit of the University of Turku. He holds a PhD in Finance, with research focused on sustainable investment. His current work explores how biodiversity considerations, particularly nature-related risks and opportunities, can be integrated into financial decision-making.

References

[1] https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/overview-sustainable-finance_en

[2] IPBES. (2019). Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services. IPBES Plenary at its seventh session (IPBES 7, Paris, 2019). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579

[3] Karolyi, G. A., & Tobin‐de La Puente, J. (2023). Biodiversity finance: A call for research into financing nature. Financial Management, 52(2), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12417

[4] Lucey, B. M., & Vigne, S. (2025). Puzzles, Tensions, and the Research Agenda for Biodiversity Finance. Financial Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/fire.70039

[5] Gjerde, S., Sautner, Z., Wagner, A. F., & Wegerich, A. (2025). Corporate nature risk perceptions. Review of Finance. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfaf050

[6] Duong, K. T., Nguyen, T. T., & Tram, H. T. X. (2025). Biodiversity risk and corporate debt maturity. International Review of Financial Analysis, 107, 104556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2025.104556

[7] Almaghrabi, K. S., Ben-Amar, W., & Kong, Z. (2025). Biodiversity risk and firms’ access to trade credit. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 105, 102226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2025.102226

[8] Garel, A., Romec, A., Sautner, Z., & Wagner, A. F. (2024). Do investors care about biodiversity? Review of Finance, 28(4), 1151–1186. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfae010

[9] Xin, W., Grant, L., Groom, B., & Zhang, C. (2025). Noisy biodiversity: The impact of ESG biodiversity ratings on asset prices. Ecological Economics, 236, 108662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2025.108662